I’ve been in nonprofit technology for a long time now – 6+ years as some form of Salesforce consultant, prior to that another 5+ as a technology manager, and in the general nonprofit industry for a decade prior to that. One of the most vexing and debilitating problems I see repeated is what’s called the “Starvation Cycle” of technology funding. I’ve experienced it personally when implementing technology for my nonprofit, and seen its outcome as reflected in cycles of Salesforce implementations as a consultant. A while back I wrote a blog about this and the necessity for a strategic approach, but in fact, even this assumes that an organization has the funding resources to be strategic at all.

The Starvation Cycle decries the notion that nonprofits even have the breathing room for a complete technology strategy in the first place, and the facts and analysis proves it. Therefore, the methodical, mission-driven approach to technology is left as an unfunded mandate or buried in a “shadow economy” of financial figures submitted to grantmakers and other funders in support of specific projects. Or, as a nonprofit colleague once told me, “Never let the truth get in the way of a good story.” Steve Anderson recently wrote a piece on what grantmakers and nonprofits can focus on to change this narrative.

The Starvation Cycle also doesn’t encompass the reality of technology implementation. If it’s true that an astoundingly high number of technology projects in for-profit organizations simply fail, 35% to 75% depending on which numbers you believe, then why would technology implementation in the nonprofit industry be any different? Too often, nonprofits are operating in a “can’t fail” environment, that not only means the funding will end when the project does, it grinds the everyday lives of staff with stress, fear, and undue expectations. It creates a negative feedback cycle that excludes, disheartens, underfunds, and exhausts everyone currently participating. It’s a cycle of madness that we have the resources to break, if we’re willing.

And thus, nonprofits are stuck forever getting resources for Year 1 technology projects, with no ability to even learn from, or even discuss, their mistakes if these projects do fail. The entire nonprofit industry suffers as an outcome, because the very knowledge necessary to understand how to better fund and implement technology is buried in obscure grant line items, not captured well from year to year, and not properly evaluated because it’s pushed under the rug if it fails. This forever perpetuates the notion that we wanted the technology, the laptops, the CRM; we got it; we ran with it until the resources ran out – licensing money, staff training money, staff hours and turnover, strategic planning money; and now, we’re back to square one looking for a new Year 1 technology solution to solve the problems engendered from an under-resourced Year 1 implementation that was denied the ability to grow into Years 2-5. The literal definition of insanity is repeating the same thing again and again and expecting different results.

As a passionate advocate of women in technology, this cycle also overwhelmingly effects women in nonprofit technology, as the gender disparity of nonprofit line staff to leadership is real and as tangible as it is for women working in the for-profit technology industry. The Starvation Cycle also stymies greater diversity and inclusion actions being attempted, where people of color, the formerly incarcerated, gender variant people, veterans, and others must climb additional hurdles before they even enter into technology in the first place.

Though if it seems like nonprofits are drowning with technology, the Starvation Cycle also explains why. In response to nonprofit technology shortcomings, we make grand attempts to help them, but often, these attempts require even greater sophistication for nonprofits to adopt. While there is a great deal of gratitude towards large and small companies who contribute donated products and licenses for their tools and platforms as part of corporate philanthropy endeavors, in some ways this is glossing over deeper needs nonprofits face when implementing these same very tools and platforms. I’d even posit that in some cases, they create more weight for organizations to lift, rather than alleviating their technological burdens, as the solution becomes a product or new technology, rather than a sustaining effort and increased organizational capacity to lead with technology.

Or, to put it another way, as I was once taught: the worst way possible to save someone who is drowning is to swim right out to them and latch on.

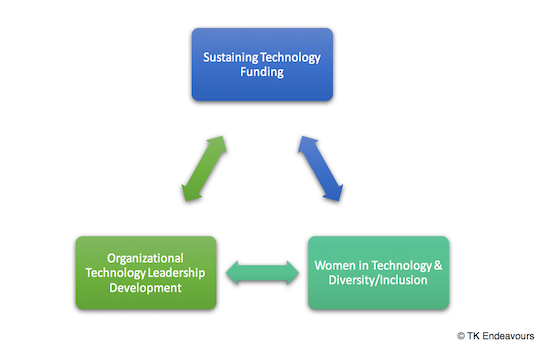

What is a better way? Here’s my hypothesis; we must continue to free grantmaking resources to focus on sustaining technology funding for the Years 2-5 and beyond of any technological implementation, while connecting them to efforts that promote sincere technology leadership and organizational development for nonprofits. And, by doing so, we will also advance the lives of thousands of women in technology, who turn up every year at conferences like the NTEN NTC and talk about this phenomenon at their own organizations. This is different from any effort made by grantmakers to date, but very connected to burgeoning discussions in the philanthropic world; and, not the same as the current tool/platform efforts being conducted by existing corporate philanthropy channels.

Sustaining technology funding requires increased technological fluency and the ability for nonprofits to genuinely lead with mission-driven technological investments. Which directly implies that it can be delivered in concert with funding support for helping nonprofits attain this fluency by investing in organizational technology leadership development and strategy, notably, technology strategy roadmaps and planning. I’ve said this at many conferences and in many forums, but for any nonprofit organizational leadership to not be as versed in technology planning as it is HR, management, and finance, is no longer acceptable.

When a nonprofit increases its overall technological fluency and ability to lead around technology, it will better support the needs of many women who are responsible for implementing and maintaining this technology – with training, certifications, and the literal time to execute their responsibilities nested in a greater organizational strategy. It will end the “accidental” technologist phenomenon permanently, as there won’t be any non-strategic technology investments.

Nonprofit technologists, especially women, who have the backing and alignment of their organization in their work will, in turn, be better capable of contributing industry-wide knowledge that will refine the myriad of problem statements and suppositions regarding providing sustaining funding in the first place.

This cycle works in the other direction as well.

Sustaining technology funding advances women in technology and diversity/inclusion efforts by contributing to the advancement of careers, knowledge, and turning the “accidental” techies into fully Intentional Techies with transferrable skills across the nonprofit industry. It’s incredibly myopic to assume that spending the necessary dollars on training and skill building for your organization’s technologist is wasted when that person leaves your organization. It contributes to the advancement of the entire nonprofit industry.

Greater support and development of women in technology, in turn, will help to break the barrier of nonprofit organizational leadership by both adding to the amount of women who have remained in the nonprofit industry and are contributing to organizational leadership, as well as imbuing nonprofit leadership with increased technological fluency.

In turn, an increased technology fluency in nonprofit leadership better understands and can articulate the ongoing needs for sustaining technology funding to peer institutions, grantmakers and donors.

I challenge any individual donor who has made a fortune in the technology industry; existing foundations; any collaboration of individual or corporate donors; and every large corporate foundation currently providing tool/platform donations to nonprofits to take up this charge. I promise, if you want to be Big Damn Heroes in the nonprofit industry, investing in the creation of a sincere, strategic, sustaining technology grantmaking program will not only allow the generous efforts of organizations like Salesforce.org to continue, but help nonprofits keep your donations with greater long-term success by providing a truly necessary complement to the good work already in progress. It’s time to step up and start a revolution.

I’ve seen (and applauded) many arguments for funding infrastructure, but nothing until now that connects the issue to equity and inclusion in this way.

To restate what I think is the main point: Investing in technology capacity – not stopping at donating products or funding the up front costs, but providing ongoing money for technology leadership and optimization – this investment is also an investment in the success of women in nonprofit technology. And an investment in tech-savvy woman leaders is an investment in the success of the whole sector. (One could substitute people of color, etc in place of women.)

I’d like to see a deeper exploration of why you believe under-funding technology disproportionately affects these groups. That connection isn’t coming through as strongly as it could.

LikeLike

Thank you! I think it boils down to the literal time available to develop the workforce we want to see. I’m working on a follow-up to this that begins with a comment from a colleague, “We’re developing all these people with nowhere to work.” It’s insufficient to give access to skills without providing for the experience required for someone to actually apply them to their job. This is a cycle that particularly effects nonprofits – high matriculation means that they’re always going to grab the least time-consuming person next, which isn’t always someone who needs to be brought into the industry with proper onboarding. Unfortunately, we’re still at the point where we are throwing bodies at the problem, and not giving nonprofits sufficient resources to actually elevate others. Thus we re-enforce the existing structures of institutional bias rather than eliminate them – because we already know that for communities who experience institutional bias, even with the proper experience, they will still be required to work much harder to attain success.

LikeLike

To give a hypothetical example: Let’s say my program director wins the lottery and resigns. I don’t have the time or money to invest in an extensive search or onboarding process, and I can’t afford to take any risks (because if my org screws up our funders will jump ship). I go through my Rolodex/network and recruit someone who seems like a safe bet and can rapidly become a productive member of the team. That all sounds logical.

But the problem is that people of color are under-represented in my close network, and I also have a bias toward feeling like I can trust people who resemble me. Not proud of this, but it’s the truth. As a result, qualified people don’t get the chance to find out about the job opportunity. And people who could excel at this job if only I had the resources to do a decent job of onboarding – they are also passed over.

This is the rationale for affirmative action, basically. And small enterprises have been exempt from that requirement because they lack resources to carry it out. Many nonprofits lack those resources too, and it’s hurting all of us in terms of diversity, equity, and organizational effectiveness.

LikeLike

Exactly – with more resources, nonprofits have more options for mindful hiring and onboarding practices. Hence, when nonprofits have more freedom and flexibility to define their basic needs through sustained technology funding (including when these needs aren’t met, or fail to be met), they can then focus on growing, retaining, and identifying the candidates who may have all the training but lack the practical experience.

LikeLike